I’ve been thinking about Joe, two Bernard’s, a couple of Georges, and sand.

February 6, 2013 | In: I've Been Thinking

On December 13, 2012, the coinventor of the bar code died at 91.

During WW II, Joseph Woodland’s military service involved being a technical assistant on the Manhattan Project in Oak Ridge, Tennessee. I’m told he thought he was working on a cure to cancer and later found out that he contributed to the development of the atomic bomb.

Sitting on a beach in 1948 (the year I was born), twenty-something Woodland found himself drawing Morse code in the sand, which he learned as a Boy Scout. That’s when he had the epiphany. Pulling his fingers down from each, he realized dots and dashes could be morphed into thick and thin parallel lines—promising a solution to a problem he’d been pondering.

Sitting on a beach in 1948 (the year I was born), twenty-something Woodland found himself drawing Morse code in the sand, which he learned as a Boy Scout. That’s when he had the epiphany. Pulling his fingers down from each, he realized dots and dashes could be morphed into thick and thin parallel lines—promising a solution to a problem he’d been pondering.

While a student at Drexel University in Philadelphia, a buddy, Bernard Silver, overheard a grocery executive challenging the dean to develop an automated system that could quickly capture product information at checkout stands. Though his appeal fell on deaf ears, it landed in the fertile soil of a young mind. Silverman told Woodland about the grocer’s request, and the two conspired to see if they could solve his problem.

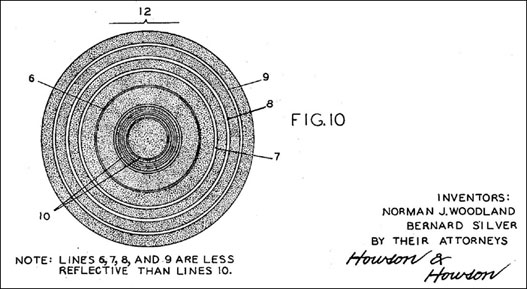

The machine-readable code they settled on was comprised of thick and thin concentric circles (think bull’s-eye) that could be scanned from any orientation. The two filed their patent in 1949, which the U.S. Patent Office awarded in 1952.

The machine-readable code they settled on was comprised of thick and thin concentric circles (think bull’s-eye) that could be scanned from any orientation. The two filed their patent in 1949, which the U.S. Patent Office awarded in 1952.

One small glitch: Optical scanners had not been sufficiently downsized to play well with checkout stands. Eventually, the young men sold their patent to Philco—for $15,000.

It wasn’t until the early 1970s, ten years after the patent expired, that an IBM work group, under Woodland’s leadership, cobbled laser technology together with the latest microprocessors to make a viable scanning system that would work at checkout.

It wasn’t until the early 1970s, ten years after the patent expired, that an IBM work group, under Woodland’s leadership, cobbled laser technology together with the latest microprocessors to make a viable scanning system that would work at checkout.

I’m guessing Joe was happy his new work involved, in the words of the prophet Isaiah, developing plowshares and pruning hooks rather than swords and spears.

In 1972, another IBM colleague, George Laurer (whom I had the privilege of interviewing at The unSUMMIT for Bedside Barcoding a few years ago) essentially sliced the bull’s-eye code from its center out to the circumference, then straightened the graphic into a rectangular rendering of vertical skinny and fat parallel lines. He called it the UPC (universal product code), and the grocery industry selected it from the numerous options presented.

The first product ever scanned for sale was a 10-pack of Juicy Fruit gum at a supermarket in Troy, Ohio, in June 1974—for a grand total of 67 cents.

Checkout would never be the same. Within ten years, virtually every item in grocery and drug stores had a bar code. Within another five (1991), not only Maalox at Walgreens and Cheerios at Safeway had UPC codes but so did dresses at Macy’s and duct tape at Home Depot. Luggage tags and baseball tickets followed. Farmers began tagging their cattle with the stripy little buggers. Scan infinitum. Bar codes everywhere on everything—except drugs in hospitals.

Checkout would never be the same. Within ten years, virtually every item in grocery and drug stores had a bar code. Within another five (1991), not only Maalox at Walgreens and Cheerios at Safeway had UPC codes but so did dresses at Macy’s and duct tape at Home Depot. Luggage tags and baseball tickets followed. Farmers began tagging their cattle with the stripy little buggers. Scan infinitum. Bar codes everywhere on everything—except drugs in hospitals.

Bar codes did not appear on hospital drugs until 1991 and then only on a dozen products. It would take another fifteen years before all drugs would have bar codes but not without an FDA rule requiring drug manufacturers to include them on all immediate packages.

Today around 60 percent of U.S. hospitals are scanning patients and medications at the point of care to verify a match. Healthcare is careening toward universal adoption. And while the rest of the world is behind, I continually learn of foreign hospitals planning and hear of numerous implementations taking place around the globe.

I tried connecting with Woodland a few years before he passed away. I wanted to thank him for his work and chat about his bar code’s success in healthcare. Unfortunately, he was not well, declining rapidly, and unable to take visitors. I don’t know if any hospital in which he was treated used bar coding, but given his Alzheimer’s, I imagine when his wristband and meds were scanned for a match, there’s a good chance he would not have traced its roots to his work. As a young man, he knew his bar code would save money. Had he foreseen how it would save lives?

In the fall of 1992, Woodland and Bill Gates were honored by President George H.W. Bush at the White House for their achievements in technology. Hard to believe, but it’s been reported that Bush appeared amazed at a demonstration of a bar-code-enabled grocery checkout demonstration he witnessed just four months earlier—in the aftermath of two decades of bar-code ubiquity. On what planet had G.W. been living? In any instance, it appears his head was in the sand?

It’s hard for me to believe there are hospitals that have not yet implemented and some that say they are not planning on implementing bar coding at the point of care. What orbit are they in? Ostriches come to mind.

If the hospital you labor in is not yet convinced, if you are planning for bar coding at the point of care, or if you are scanning veterans and want to learn how to improve and expand your use of Woodland’s seminal invention, I urge you to attend The unSUMMIT for Bedside Barcoding this April 24-26. We will be meeting a few hours up the Interstate from Miami Beach, where Woodland had his epiphany in the sand, at the beautiful Renaissance Orlando at Sea World. Check out the brochure.

Its pretty cool that we get to extend the benefits of Woodland’s life work.

Thanks, Joe.

Mark Neuenschwander aka Noosh

BTW Recently in NYC, I connected with famed artist Bernard Solco, the guy who painted the Kodachrome bar code that hangs in my office.

BTW Recently in NYC, I connected with famed artist Bernard Solco, the guy who painted the Kodachrome bar code that hangs in my office.

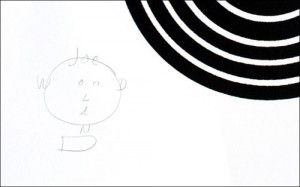

In late 1999, he was commissioned by the Association for Automatic Identification and Mobility to paint the bull’s-eye for the a 50th anniversary of its invention. Woodland proudly and playfully autographed the limited edition prints. I am fortunate to possess one.

You gotta love Woodland’s quirky signature. It goes back to a kindergarten assignment. The teacher asked her children to draw pictures using the letters of their names. That he used it to sign these historic prints, further confirms what I have heard from a few of his IBM colleagues—the engineer was as fun as he was brilliant.

You gotta love Woodland’s quirky signature. It goes back to a kindergarten assignment. The teacher asked her children to draw pictures using the letters of their names. That he used it to sign these historic prints, further confirms what I have heard from a few of his IBM colleagues—the engineer was as fun as he was brilliant.

1 Response to I’ve been thinking about Joe, two Bernard’s, a couple of Georges, and sand.

Michelle Foreman, RPh

February 7th, 2013 at 10:44 am

I love touchy-feely stories like these….